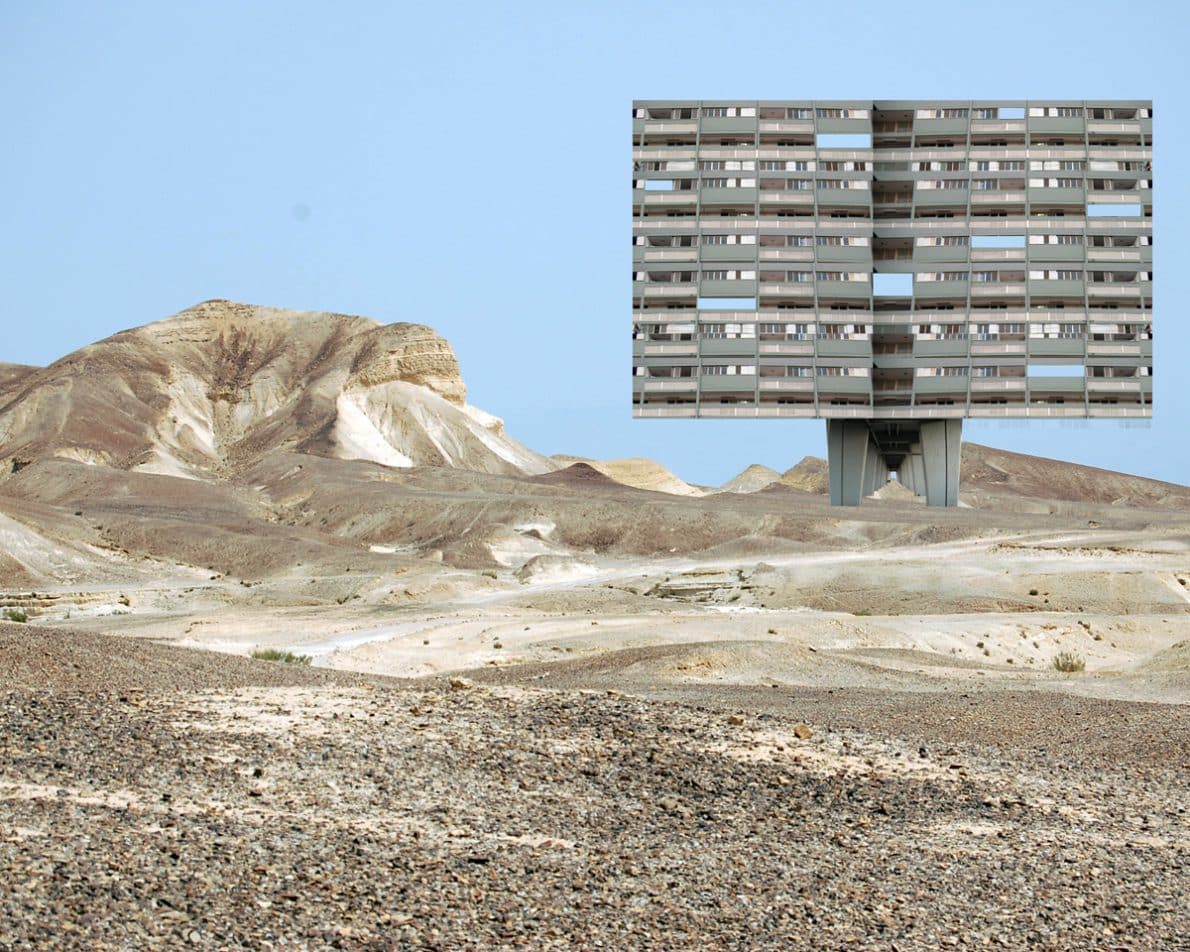

Modern Be’er Sheva was built by the state of Israel as the Negev’s capital city and as a symbol of making the desert bloom.

Modern Be’er Sheva was built by the state of Israel as the Negev’s capital city and as a symbol of making the desert bloom. As a result, Be’er Sheva received a specific architectural language and, particularly in its major buildings, a symbolic aspect beyond functional importance. The style chosen for its architecture was Brutalism, an architectural style stemming from 1950s Western Europe – chiefly France and the United Kingdom – and by the 1970s it became prevalent world-wide.

The chief traits of the Brutalist style are the use of raw concrete (in French, béton brut), with formal richness and daring both in the structure’s design and its shell. Compared with the International Style that preceded it (known in Israel as the Bauhaus style), typified by it smooth and uniform white plaster façades and minimal use of geometric forms, Brutalism is identifiable by its rugged grey façades and extreme sculptural freedom.

Brutalism’s formal language was more than a design caprice on the part of the post-WWII generation of architects, who rebelled against their predecessors. It derived from a cogent architectural ethic and doctrine; an ethic that had abandoned hope of retrieving the orderly world of prewar Europe, and now sought truth and authenticity without ornamentation. So Brutalism aimed to show the structure’s truth, not to cover it with plaster; to disclose the process and effort entailed in building it; and to presence simple construction materials – chiefly concrete.

Inspired by those values, Brutalism’s architects aspired to create new patterns of residential blocks that would reflect the Welfare State’s principles but would also evoke the memory of the streets, squares, and markets of pre-Modern architecture. They proposed architecture that would not only offer housing solutions, but also generate communities that the structure defines and embraces. Brutalist public buildings were aimed at lauding the welfare state, which constructs hospitals, universities, and synagogues for its citizens. They were also intended to speak to the public through symbolic, even monumental, motifs that were very different from the abstract and alienated modernist architecture.

Buildings in the Brutalist style were characteristic of public construction throughout Israel, and was considered a ‘sabra – native-born’ style – rough but straightforward, power-driven yet daring. Be’er Sheva is a unique and riveting example of Israeli and international Brutalism. The best architects from the founding generation – Jacob Rechter, Ram Carmi, Eldar Sharon, Nahum Zolotov, Lufenfeld-Gamerman, Yasky-Alexandroni, and later Yasky-Gil, Nadler & Nadler -Bixon-Gil – all built major projects in Be’er Sheva, applying tremendous thought and effort. Because the state was a pivotal factor in the city’s construction, Brutalism’s presence in the city is more notable and central than in other cities and fabrics in Israel that were principally designed by the private sector which tended not to design in that style. Moreover, the desert landscape, the hot climate, and historical precedents of desert construction engendered distinctive architectural motifs, in turn creating a valuable local dialect of Israeli and world-wide Brutalism. Among them are the sealed perforated facades of Be’er Sheva’s Municipality building, and the tent motif of the Bavli Synagogue.

Since the wave of privatization in the 1970s, the Brutalist style has been replaced by other architectural approaches. Many Brutalist buildings, in Israel and elsewhere, have been harshly criticized, scorned, and forgotten. And yet, over the past decade there’s been a surge of interest and curiosity about the Brutalist legacy.

Dreaming in Concrete is an exhibition intended to generate appreciation for that legacy of raw concrete construction and the Brutalist style of Be’er Sheva. We hope it will become a source of pride and local identity, and recognition of the qualities of the city’s buildings. In tandem with identifying the errors and flaws that accompanied them, we can create a set of anchors for urban renewal, where the existing architectural heritage is an asset and catalyzer for processes of urban and cultural renaissance.

Guest curators:

Hadas Shadar, Eran Tamir Tawil, Omri Oz Amar

Nirit Dahan

Shlomi Ara, Gabriel Benaim, Yael Itzkin, Eli Singalovski and

Sharon Yokev

Be'er Sheva municipality

Kivunim

Ministry of Culture and Sport